Research

energy, climate, development, networks, industrial organization, firms

2025

-

Balancing Climate and Industrial Objectives when Pricing Dirty Upstream GoodsEugene Tan2025

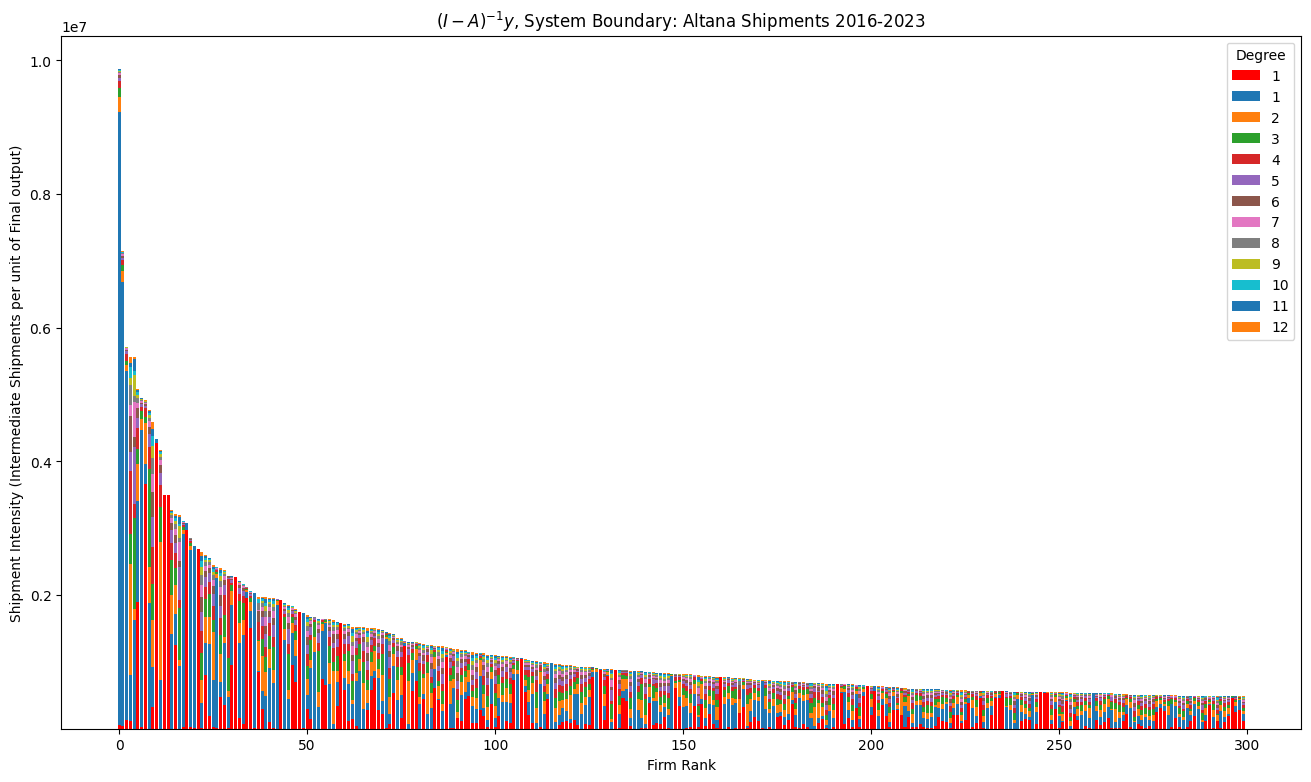

Balancing Climate and Industrial Objectives when Pricing Dirty Upstream GoodsEugene Tan2025Most upstream goods are dirty, and most industrial emissions are upstream. A Pigouvian logic would tax dirty goods to internalize their negative externalities, whereas industrial economists have advocated for subsidies on upstream goods to fix accumulated quantity distortions in vertically integrated supply chains. Should we subsidize or tax dirty upstream goods? While ‘direct’ abatement and leakage occur through the adoption of green or abatement technologies and relocation, respectively, the ‘indirect’ effects of carbon pricing depend on the microeconomic responses of buyers exposed to regulated suppliers. Buyers can choose to substitute towards green suppliers (indirect abatement), source from foreign suppliers (indirect leakage), pass through costs down their supply chain, or exit. Pass-through and exit propagate the regulatory costs downstream, creating the same choice for downstream producers. If indirect abatement is minimal and pass-through dominates, carbon pricing may function as a de-facto negative industrial policy. Using novel production network data, I analyze the effects of EU-ETS price shocks on buyer substitution and cost pass-through. The behavior of buyers in a production network tends to raise the social costs and reduce the social benefits of regulation. In a second-best world, climate policy should be designed with market imperfections in mind.

-

Connection Policy Design for Electricity Access: Lessons from Rwandan ElectrificationEugene Tan, Gabriel Gonzalez Sutil, and Joel Mugyenyi2025

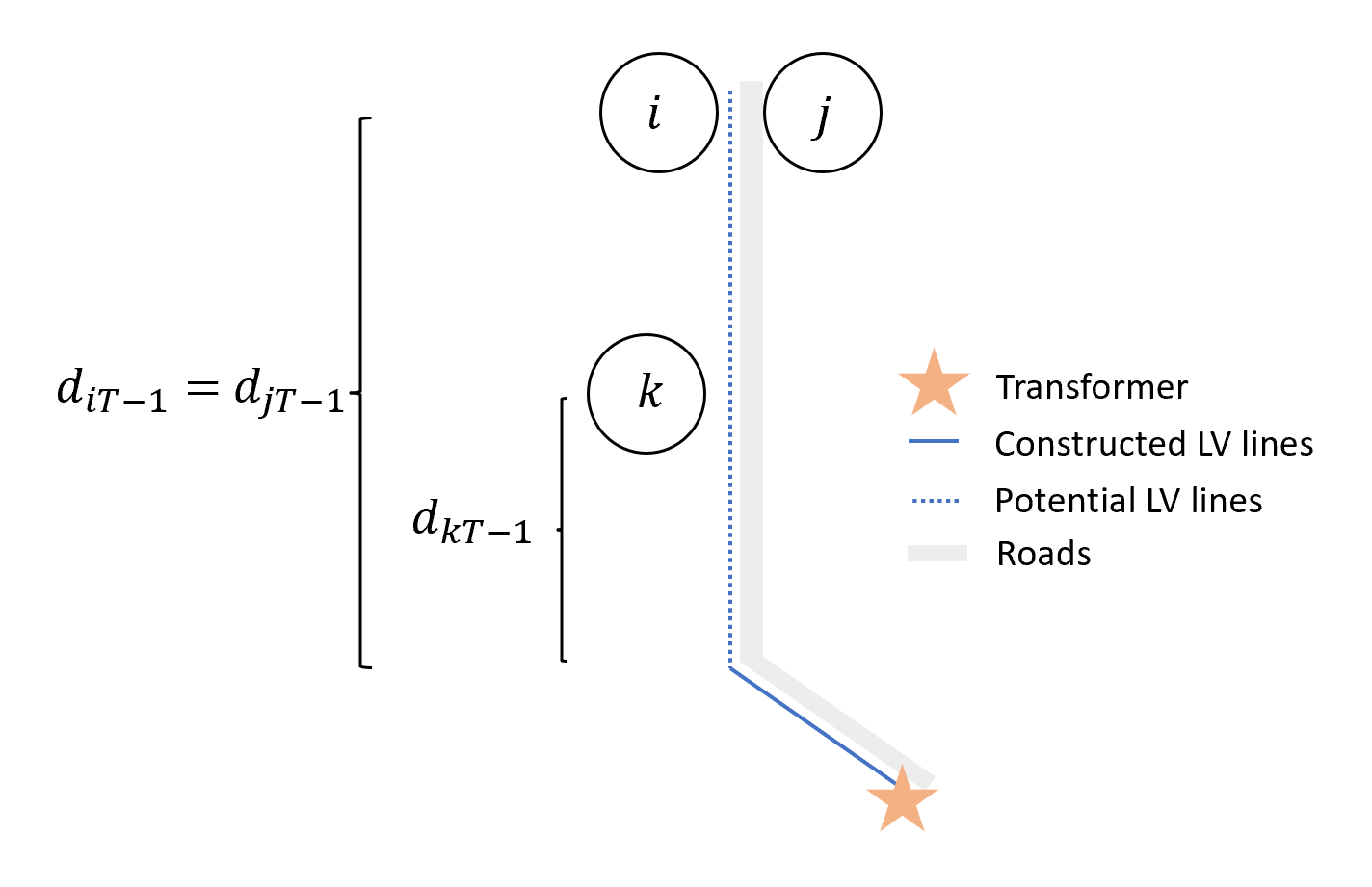

Connection Policy Design for Electricity Access: Lessons from Rwandan ElectrificationEugene Tan, Gabriel Gonzalez Sutil, and Joel Mugyenyi2025Sub-Saharan utilities and governments have adopted retail electricity connection policies unused elsewhere to expand electricity access. We study three such novel policies: credit repaid through consumption rather than fixed installments; spatial delineation of operating areas between on-grid utilities and off-grid solar providers; and connection charges where consumers pay a portion of the marginal cost of the materials for network expansion based on their distance to the existing grid. The most novel are distance-based connection charges, which create strategic incentives for connecting to the grid. When the first household to connect pays for a connection, the utility extends the grid in response, so en-route and downstream neighbors benefit from lower connection costs via the policy. On one hand, this is a positive externality that creates free-riding incentives and slows adoption. On the other hand, richer first-adopters tend to connect first, making it a cross-subsidy to their poorer neighbors. From the utility’s perspective, the cross-subsidy is a price discrimination mechanism that increases utility revenue and expands electricity access in equilibrium relative to a flat-fee charge where every type of consumer pays the same price. Using a case study of Rwanda, we develop a novel algorithm to reconstruct the historical grid state at each point in time. We adapt peer-of-peer instruments from social network econometrics to physically evolving infrastructure networks to address the reflection problem, then estimate a dynamic structural model with a graphical state space that exploits the hierarchical structure of distribution grids. We find evidence of strategic behavior under distance-based connection charges: a neighbor’s connection decreases contemporaneous adoption probability by 8% because of free-riding but permanently increases subsequent adoption by 4.6%. Our counterfactual simulations suggest that replacing Rwanda’s distance-based charges with a flat-fee charge based on Kenya’s policies would halve rural electricity access. Along the way, we show that credit and spatial delineation policies are significantly more costly than distance-based charges in increasing electricity access.

-

Measuring Embedded Emissions Without Direct Firm DisclosureEugene Tan2025

Measuring Embedded Emissions Without Direct Firm DisclosureEugene Tan2025Can we measure embedded emissions without direct firm disclosure? Firm disclosure of scope 3 emissions is difficult because firms typically know only a small fraction of the emissions of their indirect suppliers, as suppliers view their own suppliers and technologies as part of their comparative advantage. We develop an algorithm to estimate intra-facility production from firm inputs and outputs based on graphical matching to technology databases, drawing from an old literature on technology-based models of the firm. We estimate life-cycle emissions from production network data, and show implications for embedded carbon-based policies.

2014

-

Energy Return on Investment (EROI) for Forty Global Oilfields Using a Detailed Engineering-Based Model of Oil ProductionAdam R. Brandt, Yuchi Sun, Sharad Bharadwaj, and 3 more authors2014

Energy Return on Investment (EROI) for Forty Global Oilfields Using a Detailed Engineering-Based Model of Oil ProductionAdam R. Brandt, Yuchi Sun, Sharad Bharadwaj, and 3 more authors2014Studies of the energy return on investment (EROI) for oil production generally rely on aggregated statistics for large regions or countries. In order to better understand the drivers of the energy productivity of oil production, we use a novel approach that applies a detailed field-level engineering model of oil and gas production to estimate energy requirements of drilling, producing, processing, and transporting crude oil. We examine 40 global oilfields, utilizing detailed data for each field from hundreds of technical and scientific data sources. Resulting net energy return (NER) ratios for studied oil fields range from ≈2 to ≈100 MJ crude oil produced per MJ of total fuels consumed. External energy return (EER) ratios, which compare energy produced to energy consumed from external sources, exceed 1000:1 for fields that are largely self-sufficient. The lowest energy returns are found to come from thermally-enhanced oil recovery technologies. Results are generally insensitive to reasonable ranges of assumptions explored in sensitivity analysis. Fields with very large associated gas production are sensitive to assumptions about surface fluids processing due to the shifts in energy consumed under different gas treatment configurations. This model does not currently include energy invested in building oilfield capital equipment (e.g., drilling rigs), nor does it include other indirect energy uses such as labor or services.